Cryptography: How Humans Hid Secrets Long Before Wi-Fi

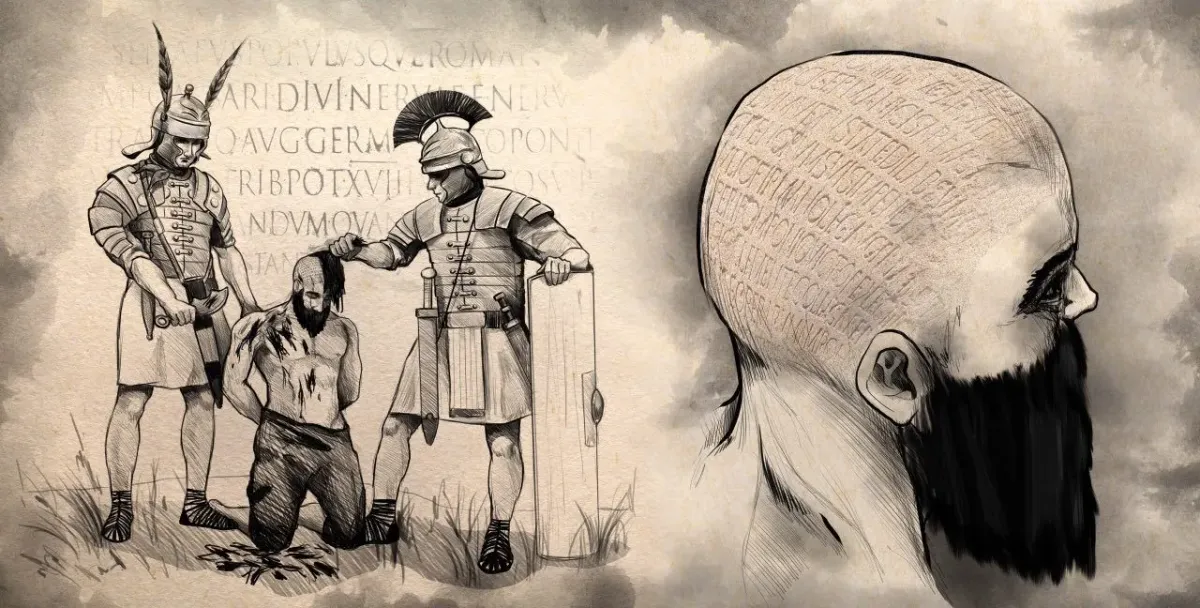

Earlier this week, my teacher told a story about a Greek ruler named Histiaeus. He shaved a trusted slave's head, pricked the message into the scalp, waited for the hair to grow back, and only then sent him off. When the slave reached Aristagoras, the ruler of Miletus, the instructions were simple: shave his head again and read what was hidden underneath.

I didn't expect a lesson about encryption to make me curious about ancient history, but it did. It also made me curious about a bigger question, if people were willing to do all that to send a secret messages, what else have humans done to protect information?

That curiosity is what made me pick up The Code Book by Simon Singh.

Cryptography In Plain Terms

So.. what even is cryptography?

At its core, cryptography is how we protect information by transforming it, so only the right person can understand it. You start with plaintext (normal text) and turn it into ciphertext (encrypted text).

Historically, most ciphers are built from two basics tricks:

Substitution - Replacing symbols with other symbols.

That can be as simple as shifting letters (like the Caesar cipher), or as complex as swapping whole chunks of text using a rule only the sender and receiver know.

Transposition - Keeping the same symbols, but changing their order.

The letters don't change, but the message becomes unreadable because the structure is scrambled.

Many real ciphers mix both ideas, because patterns are the enemy: once codebreakers learn what to look for, a cipher can go from mysterious to obvious surprisingly fast.

The shaved-head story is different, that isn't cryptography, it's steganography: Hiding the existence of a message in the first place. The goal isn't to make the message unreadable, but to make it unnoticed.

And that’s what makes the history of secret communication so fun, humans have always mixed creativity, psychology, and technology to outsmart whoever might be watching.

Stories From The History of Secrecy

Steganography didn't stop with shaved heads. In the code book, Singh mentions all sorts of ways people tried to make a message invisible.

One example is from ancient China: A message written on a tiny piece of silk, scrunched into a small ball, and sealed in wax. Small enough that a messenger could swallow it to get past guards.

Another trick was to write on the wooden base of a wax tablet, then cover it with fresh wax so it looked blank until the recipient knew to scrape it open.

But hiding a message only works until people start searching. After that, the book shifts from hiding messages to encrypting them.

Simple substitution ciphers (like the Caesar cipher) are easy to use, but they created a new arms race: once codebreakers learned to look for patterns in language, many “secret” messages stopped being secret. That’s why more advanced systems like the Vigenère cipher became famous. It wasn’t just one alphabet shift, but many, and for a long time people believed it was unbreakable… until it wasn’t.

Machines Change Everything: Enigma

During World War II, Nazi Germany used the Enigma machine (a complex encryption device) to secure military communications. Enigma took encryption from something you could do with a pencil to something that could be done quickly and repeatedly, at massive scale.

Instead of one fixed substitution, Enigma used rotating wheels (rotors) that changed the substitution constantly while you typed. That meant the same letters could encrypt differently each time, which make simple pattern-hunting much harder.

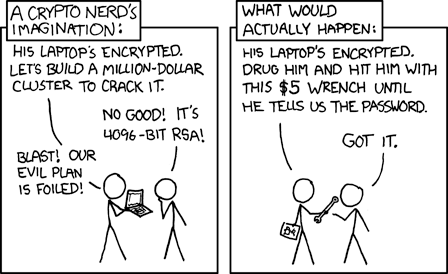

But Singh's point is that "hard to break" isn't the same as "unbreakable". Enigma wasn't defeated by one simple solution, it was defeated by a combination of math, engineering, captured information, and human mistakes. When you're sending thousands of messages a day, small habits and predictable phrases can become weaknesses.

The Math Era: Sharing Secrets Without Meeting

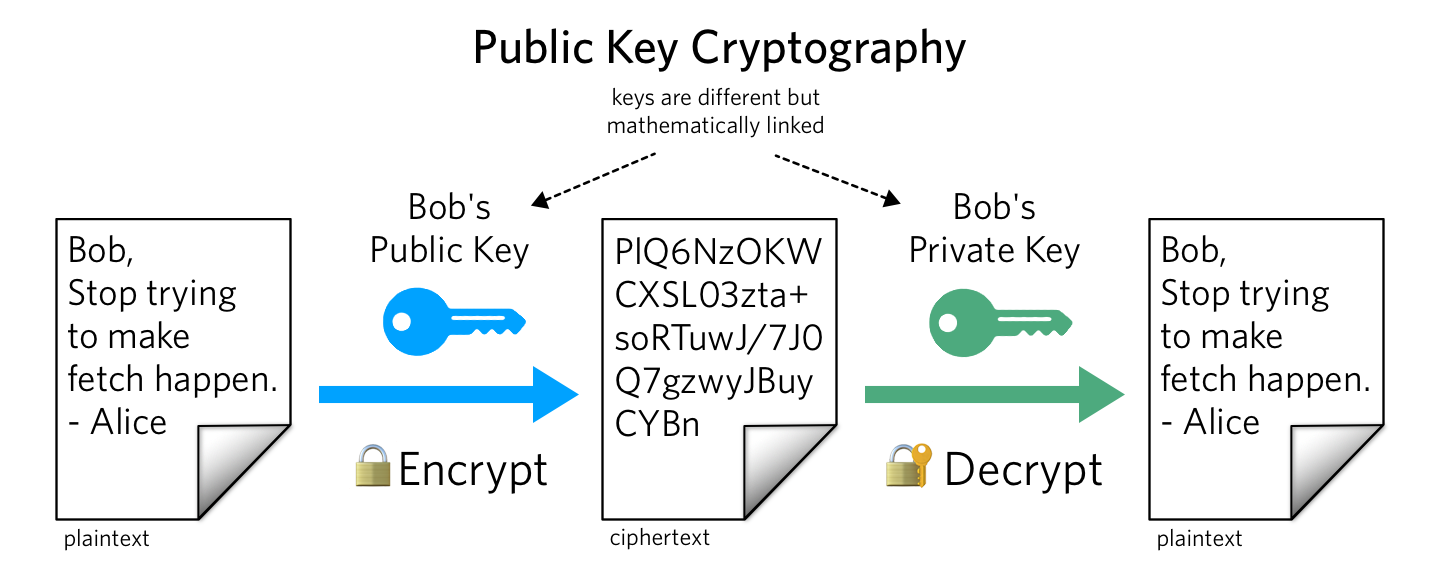

After World War II, cryptography slowly moved from machines to mathematics. One of the biggest ideas in the book is public-key cryptography. The weird-sounding concept that you can publish one key for the whole world to use, while keeping another key private, and the private one is the only thing that can unlock what the public one locks.

That single idea solves a huge problem: secure communication with strangers. This is the idea behind systems like RSA, and later tools like PGP that brought strong encryption to regular people, not just governments.

Where We Are Now (And What's Next)

Today, encryption isn't just for spies and generals, it's everywhere. When you log in, pay online, or message someone privately, you're relying on cryptography working quietly in the background.

Modern systems often use Hybrid Encryption. They combine the best of both worlds - public-key methods are used to securely exchange a "session key," and then fast, symmetric methods (like AES) handle the actual data transfer. This makes our connections both incredibly secure and very fast.

Singh ends by looking forward, too. If powerful quantum computers become practical, they could threaten some of the public-key methods we rely on today, which is why researchers are already building and standardizing "post-quantum" alternatives.

Final Thoughts

This book made cryptography feel real, not just something computers do, but something humans have struggled with for centuries. What stuck with me was the bigger idea that secrecy is a constant back-and-forth between people who hide information and people who try to uncover it.

I highly recommend this book if you enjoy clever historical stories and want to understand the ideas behind encryption in a way that actually sticks.

Oh, and if you want a quick feel for what a cipher does, try this! The code below encrypts “HELLO WORLD” using three famous historical methods.

import string

def caesar_cipher(plaintext, shift):

alphabet = string.ascii_uppercase

ciphertext = ""

for char in plaintext:

if char in alphabet:

index = (alphabet.index(char) + shift) % 26

ciphertext += alphabet[index]

else:

ciphertext += char

return ciphertext

def vigenere_cipher(plaintext, key):

alphabet = string.ascii_uppercase

key = key.upper()

key_len = len(key)

key_pos = 0

ciphertext = ""

for char in plaintext:

if char in alphabet:

shift = alphabet.index(key[key_pos]) % 26

index = (alphabet.index(char) + shift) % 26

ciphertext += alphabet[index]

key_pos = (key_pos + 1) % key_len

else:

ciphertext += char

return ciphertext

def playfair_cipher(plaintext, key):

alphabet = string.ascii_uppercase.replace("J", "")

key = key.upper().replace("J", "I")

key_len = len(key)

key_pos = 0

grid = ""

for char in key + alphabet:

if char not in grid:

grid += char

grid_len = len(grid)

if grid_len < 25:

for char in alphabet:

if char not in grid:

grid += char

ciphertext = ""

plaintext = plaintext.upper().replace("J", "I")

plaintext_len = len(plaintext)

plaintext_pos = 0

while plaintext_pos < plaintext_len:

char1 = plaintext[plaintext_pos]

if char1 not in alphabet:

plaintext_pos += 1

continue

char2 = plaintext[plaintext_pos + 1] if plaintext_pos + 1 < plaintext_len else "X"

if char2 not in alphabet:

plaintext_pos += 2

continue

if char1 == char2:

char2 = "X"

plaintext_pos -= 1

row1, col1 = divmod(grid.index(char1), 5)

row2, col2 = divmod(grid.index(char2), 5)

if row1 == row2:

ciphertext += grid[row1 * 5 + (col1 + 1) % 5]

ciphertext += grid[row2 * 5 + (col2 + 1) % 5]

elif col1 == col2:

ciphertext += grid[((row1 + 1) % 5) * 5 + col1]

ciphertext += grid[((row2 + 1) % 5) * 5 + col2]

else:

ciphertext += grid[row1 * 5 + col2]

ciphertext += grid[row2 * 5 + col1]

plaintext_pos += 2

return ciphertext

# Example usage:

plaintext = "HELLO WORLD"

shift = 3

key = "CRYPTO"

playfair_key = "KEYWORD"

caesar_ciphertext = caesar_cipher(plaintext, shift)

vigenere_ciphertext = vigenere_cipher(plaintext, key)

playfair_ciphertext = playfair_cipher(plaintext, playfair_key)

print("Caesar ciphertext:", caesar_ciphertext)

print("vigenere ciphertext:", vigenere_ciphertext)

print("playfair ciphertext:", playfair_ciphertext)Output:

Caesar ciphertext: KHOOR ZRUOG

vigenere ciphertext: JVJAH KQIJS

playfair ciphertext: GYIZSCOKCFBU